- Home

- Admin

- Meetings

- Fry-Ark Project

- Projects

- Water Management

- Agriculture Conservation

- Arkansas River Basin Water Rights

- Conservation Plans

- Conservation & Education

- Education

- Fryingpan-Arkansas Project Water Import Tracking

- Inclusion into the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District

- Legislation

- The Allocation of Fryingpan-Arkansas Project Water & Project Water Return Flows

- RRA

- Snow Pack Monitoring

- Water Conservation BMP Tool Box

- Winter Water Storage

- Water Wise Gardening

- Login

Water Loss Control

Water loss control encompasses those practices and programs that a utility should be conducting consistently throughout the year to create a culture of efficient water resources management from production to tap—including key tasks of daily data collection, management and assessment; infrastructure maintenance and updating; leak detection and management; and annual water auditing. Utilities are obligated to conduct water loss control practices and programs in a standardized, proactive manner - that utilitzes best practices that are economically justifiable and appropriately mindful of the limitations of the resource. Only with accurate, current, utility specific data can assessments be made by the organization that support business decision-making and protect the interests of the rate payers. For this reason, water loss control is a continuous process that is integrally linked to the planning activities that are conducted on a regular basis by the utility.

There are four primary reasons for strong water loss control procedures:

- To limit unnecessary or wasteful source water withdrawals;

- To optimize revenue recovery and promoting equity among ratepayers;

- Minimize distribution system interruptions, optimizing supply efficiency and generating reliable performance data; and

- Maintain system integrity.

Specific benefits include:

- Reducing apparent losses

- Reducing real losses

- Improving data integrity

- Better use of water resources

- Increased knowledge of distribution system

- Increased knowledge of customer water use, and metering and billing systems

- Safeguarding public health

- Improved public relations

- Reduced liability

- Reduce disruption to customers

- Improves reviews from financial community

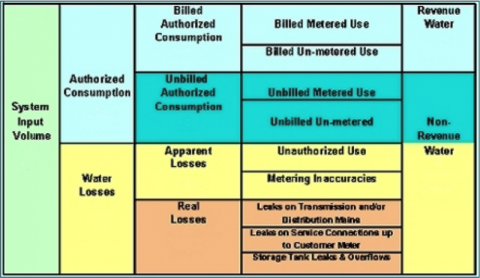

Water utilities have long suffered from a variety of losses and inefficiencies related to providing potable water to their customers. According to the AWWA, most operators recognize piping distribution system leakage, categorized as real losses, as a primary type of loss. However, water suppliers also suffer losses from poor accounting, meter inaccuracies and unauthorized consumption. These losses are collectively labeled apparent losses. Both real and apparent losses have a negative impact on revenue and consumption data accuracy. It is essential that system operators employ means to control these losses.

A survey was conducted for the AWWA in 2002, which found that water utilities use widely varying language and methods to track what many call unaccounted for water, and that the use of this term is vague and subject to interpretation. For example, many utilities have routinely included volumes of known leaks in accounted for water, thus underestimating actual leakage or real losses. In attempting to gather voluntary data from large water utilities, one state agency found that water utilities that earnestly attempt to audit their supplies report real and apparent losses that are less flattering than counterparts that reported unrealistically low losses with no substantiation of their data (McNamee, 2002).

This type of gamesmanship reflects poorly on the US water industry, however, the AWWA has developed a better system of accounting for water utilities to detect and repair systems with both real and apparent losses.

The recommended system of water loss accounting includes two key tasks – data collection (through specific auditing methods) and data analyses (using water balance calculations). Each of these is described further in the next level of the Tool Box.

Implementation of a system-wide water audit focuses upon quantifying customer consumption and volumes of real and apparent losses based on the best practice developed in 2000 by IWA/AWWA Water Audit Method[1]. The method that was developed by the AWWA allows the operator to reveal the destinations of water supplied throughout the distribution system and to quantify volumes of consumption and loss. Imperative to the success of this method is a robust set of data that characterizes meter accuracy and all those components of water use that are described in the figure provided below.

The AWWA Water Audit methodology promotes a process of data collection and assessment that leads to the characterization of real and apparent losses; providing the water utility with a map of needs and potential programs that can improve water distribution and billing efficiencies. The process involves evaluating:

- Production supply

- Billings

- Apparent losses

- Real losses

In accordance with AWWA recommendations, a system wide water audit should be conducted annually by consciencious water utilities to support water loss control. The complete water audit methodology is an eleven step process detailed in this table.

There are three levels of recommended auditing procedures, each adding increasing refinement. Most utilities should begin with the top-down approach, as described below, before proceeding to more complex and rigorous programs. Beginning with the top-down approach, an operator can assess the status of data availability and information required to support more refined analyses, such that future auditing can be performed after improvements are made to data collection processes and procedures (see data collection and management BMPs).

Regardless of which audit method that is used, utilities should utilize the AWWA auditing software (descibed in the Data Analysis Section of this BMP) to help standardize their data collection and reporting, and allow for the consistent tracking of wate loss information within and between utilities.

Top Down Approach – the initial desk-top process of gathering and analyzing information from existing records, procedures, data, and other information systems. Key data collection for this level of analysis includes water production and treatment volumes (preferably on a daily to monthly basis), customer water delivery records (preferably on a monthly basis), metered, unbilled water use (preferably on a monthly basis), and estimates of unmetered water uses. A key set of assumptions that typically will need to be made to conduct these types of audits will be the percent of customer meter and production, master meter inaccuracies.

Component Analysis – This audit method expands the data collection from the top-down approach to include developing estimates for leakage volumes based on the nature of leak occurrences and durations. This technique can also be used to model various occurrences of apparent losses by looking at the nature and duration of estimated real loss.

Bottom-Up Approach – This technique is used to validate the top-down results with actual field measurements such as leakage losses (calculated from integrated zonal or district metered area night flows). Field data is also collected to determine meter accuracy via physical inspections of customer properties to characterize apparent losses from inaccurate, defective, or vandalized customer meters, and to identify unauthorized consumption. Finally, process flowcharting of customer billing systems can be used to identify systematic billing errors.

Once the water audit data has been collected, a water balance calculation is developed to characterize water losses – both real and apparent – to the extent feasible. A preliminary assessment of water loss can be obtained by gathering available records and placing data into the water audit worksheet such as is available on the AWWA website at http://www.awwa.org/resources-tools/water-knowledge/water-loss-control.aspx. The summary data from the water audit is shown in the water balance, which compares the distribution system input volume with the sum of customer consumption and losses (estimated and known).

A simplified table, shown below, may also be used for small systems.

Example of a Simplified Water Balance

|

Category |

Estimated Value |

Data Validity Score |

Comment |

|

Water Supplied |

(in 1000 gallons) |

(grade 1 to 10) |

(related to the grading) |

|

Produced Groundwater |

15,112 |

9 |

100% of water sources are metered |

|

Master Meter Accuracy |

.97 |

2 |

Daily production readings scribed on paper, no adjustment for changes in storage volumes |

|

Total Water Supplied |

15,577 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Authorized Consumption |

|

|

|

|

Billed Metered |

8,926 |

6 |

Manual meter reading, limited meter accuracy testing |

|

Billed Unmetered |

0 |

2 |

Written policies do not exist for tracking billed unmetered accounts |

|

Unbilled Metered |

0 |

2 |

Written policies do not exist for tracking unbilled metered accounts |

|

Unbilled Unmetered (a listing of some unmetered uses are provided in the table below) |

447 |

4 |

Extent of unbilled unmetered partially known and some procedures exist to document uses (e.g., fire hydrant flushing, filter backwash) |

|

Total Authorized Consumption |

9,373 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Water Losses |

|

|

|

|

Total Water Loss |

|

|

|

|

= Total Water Supplied – Total Authorized Consumption |

6,204 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Apparent Losses |

|

|

|

|

Unauthorized Consumption |

0 |

2 |

Unauthorized consumption is not known or tracked |

|

Customer Meter Inaccuracies |

893 |

4 |

Reliable recordkeeping exists; meter information is improving as meters are replaced. Meter accuracy testing is conducted annually for a small number of meters. Limited number of oldest meters replaced each year. Inaccuracy volume is largely an estimate, but refined based upon limited testing data. |

|

Systematic Data Handling Errors |

0 |

4 |

Policy and procedures for permitting and billing exist but needs refinement. Computerized billing system exists, but is dated or lacks needed functionality. Periodic, limited internal audits conducted and confirm with approximate accuracy the consumption volumes lost to billing lapses. |

|

Total Apparent Losses |

893 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real Losses (Current Annual Real Losses (CARL)) |

|

|

|

|

CARL = Total Water Loss – Total Apparent Losses |

5,311 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-Revenue Water |

|

|

|

|

= Total Water Loss + Unbilled Metered + Unbilled Unmetered |

6,651 |

|

|

Note that the power of the water balance calculation lies in the earnest evaluation of those data used to character water quantities. Estimated values may be used to support completion of the task, however, the operator must be aware of the limitations of any analysis completed based on estimates. It is suggested that for best results, the operator should test variations in estimated values, to characterize potential ranges of real and apparent losses based on unknown or unattainable information. For example, if the volume of unmetered water is not known, the operator can estimate ranges for unmetered water based on expected uses (see table below for unmetered water uses identified during previous water audits conducted for small water users in the lower Arkansas River Valley.

Note that one of the attributes of the AWWA Audit Tool relates to tracking the quality of the data being collected and used by the utility in developing the water audit and calculating water loss. Water auditing, although a vital part of any utility water loss program, is still in its infancy as a best practice for most utilities - large and small. Therefore, grading current data quality, and making improvements to data quality over time, is one key objective to the overall water audit approach as recommended by AWWA.

Additional discussions of the development and use of these audit data and calculation are provided in the Water Distribution Data Collection and Management section of the BMP Tool Box .

Selected Unmetered Water Uses Identified in the Lower Arkansas River Basin

|

Church |

Other Water Treatment Plant Uses |

|

Construction Water (from hydrants and/or standpipes) |

Street Cleaning |

|

Filter Backwash |

Sewer Collection Cleaning |

|

Fire Suppression |

Town Hall |

|

Firehouse |

Town Shop |

|

Hydrant and Line Flushing |

Town/City Parks |

Note that one of the attributes of the AWWA Audit Tool relates to tracking the quality of the data being collected and used by the utility in developing the water audit and calculating water loss. Water auditing, although a vital part of any utility water loss program, is still in its infancy as a best practice for most utilities - large and small. Therefore, grading current data quality, and making improvements to data quality over time, is one key objective to the overall water audit approach as recommended by AWWA.

Selected Unmetered Water Uses Identified in the Lower Arkansas River Basin

|

Church |

Other Water Treatment Plant Uses |

|

Construction Water (from hydrants and/or standpipes) |

Street Cleaning |

|

Filter Backwash |

Sewer Collection Cleaning |

|

Fire Suppression |

Town Hall |

|

Firehouse |

Town Shop |

|

Hydrant and Line Flushing |

Town/City Parks |

[1] American Water Works Association, Water Audits and Loss Control Programs, Manual M-36, 2009, AWWA, Denver, CO 80235

Billing is the most common interaction between the water utility and its customers; and it is the most critical part of the relationship, since for any organization, revenue generation is paramount to sustainability, for without cash flow, the utility cannot meet its financial obligations. Therefore, billing practices and protocols are a vital component of any utility’s operations. Billing also can be used to provide important messaging to the customer – especially messaging related to over use of water. However, messages contained in a water bill related to the over use of water is best provided to a customer within a short time of actual water use such that a behavioral change can be implemented. Timely billing for water use to create positive cash flow for the utility and to provide customers with feedback on their water use is an important tool for utilities to use to maintain fiscal independence and to help instill a culture of water use efficiency.

Resources

American Water Works Association Water Loss Control Page with Link to Free Software

American Water Works Association M-36 Manual (Water Audits and Loss Control Programs)

EPA Control and Mitigation of Drinking Water Losses in Distribution Systems