- Home

- Admin

- Meetings

- Fry-Ark Project

- Projects

- Water Management

- Agriculture Conservation

- Arkansas River Basin Water Rights

- Conservation Plans

- Conservation & Education

- Education

- Fryingpan-Arkansas Project Water Import Tracking

- Inclusion into the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District

- Legislation

- The Allocation of Fryingpan-Arkansas Project Water & Project Water Return Flows

- RRA

- Snow Pack Monitoring

- Water Conservation BMP Tool Box

- Winter Water Storage

- Water Wise Gardening

- Login

Planning

All organizations that provide sustainable water supply to their community must undertake a certain level of planning to prepare for the future. Planning involves utilizing resources to think about and organize activities to achieve a certain goal. To this end, planning includes data organization and assessment, goal setting, and alternative evaluations, even if they are performed in a rudimentary manner.

Insomuch as meanful water conservation and water use efficiency effect cash flow, water supply options and needs, carry-over storage opportunities, and water sales revenue, water conservation should be considered during all stages of planning as defined and descibed below.

Key types of plans that all utilities should consider performing on a regular, if not annual, basis, include the following:

An annual budget outlines both the income and expenditures that are expected to be received and paid over the coming year. It is important for organizations to create accurate and up-to-date annual budgets in order to maintain control over their finances, and to show funders exactly how their money is being used. How specific and complex the actual budget document needs to be depends on how large the budget is, how many funders you have and what their requirements are, how many different programs or activities you're using the money for, etc. At some level, however, your budget will need to include the following:

- Projected expenses. The amount of money you expect to spend in the coming fiscal year, broken down into the categories you expect to spend it in -- salaries, office expenses, etc.

- Projected income. The amount of money you expect to take in for the coming fiscal year, broken down by sources -- i.e. the amount you expect from each funding source, including not only grants and contracts, but also your own fundraising efforts, memberships, and sales of goods or services.

- The interaction of expenses and income. What gets funded from which sources? In many cases, this is a condition of the funding: a funder agrees to provide money for a specific position, for instance, or for particular activities or items. If funding comes with restrictions, it's important to build those restrictions into your budget, so that you can make sure to spend the money as you've told the funder you would.

- Adjustments to reflect reality as the year goes on. Your budget will likely begin with estimates, and as the year progresses, those estimates need to be adjusted to be as accurate as possible to keep track of what's really happening.

Resources

http://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/annual-budget.asp#axzz2NcKOdQ2V

Capital Improvement Plan (Program), or CIP, is a short-range plan, usually four to ten years, which identifies capital projects and equipment purchases, provides a planning schedule and identifies options for financing the plan. A capital improvements program is composed of two parts — a capital budget and a capital program. The capital budget is the upcoming year's spending plan for capital items (tangible assets or projects that cost at least $10,000 (or some other agreed upon cost ceiling) and have a useful life of at least five years). The capital program is a plan for capital expenditures that extends five years beyond the capital budget.

A complete, properly developed CIP has the following benefits:

- Facilitates coordination between capital needs and the operating budgets.

- Enhances the utility's credit rating, control of its tax rate, and avoids sudden changes in its debt service requirements.

- Identifies the most economical means of financing capital projects.

- Increases opportunities for obtaining federal and state aid.

- Relates public facilities to other public and private development and redevelopment policies and plans.

- Focuses attention on community objectives and fiscal capacity.

- Keeps the public and the utility’s customers informed about future needs and projects.

- Coordinates the activities of neighboring and overlapping units of local government to reduce duplication.

- Encourages careful project planning and design to avoid costly mistakes and help a utility reach desired goals.

Resources

Water supply planning is a comprehensive plan that evaluates the status and sustainability of water supply available to a specific utility or group of utilities, including how water will be supplied to the utility’s customers and how the water supply will be managed. Water supply planning for water utilities traditionally relies on system and financial planning processes internal to the utility, and emphasizes ownership and control of water resources (e.g., groundwater withdrawals). Water supply planning also incorporates assessment of utility ownership of the water delivery infrastructure (plants, pipes, and so on). For these reasons the water supply plans are excellent precursors to the assessment of facility needs and the development of a capital improvement plan.

The typical scope for a water supply plan includes the following;

- Create summary of available water supply including description of all surface and groundwater supplies, alternative supplies, and expected yield, based on historical data.

- Develop forecast of future water supply demand.

- Identify water supply infrastructure limitations and needs based on future demands.

- Develop listing of infrastructure improvements and water development needs based on assessment of water availability, current infrastructure limitations and projected future demands.

Water conservation planning is used to evaluate the need and costs for utility water conservation based on forecasted demands, available water supply and limitations in water availability, infrastructure and resources. Based on several key water efficiency literature sources and the extensive experience of many water conservation professionals, the Colorado Water Conservation Board has established five planning steps to facilitate effective conservation planning. Implementation of these five steps will likely be varied for the many different water utilities that may choose to perform water conservation planning across Colorado given variations in water sources, customer make-up, age of infrastructure, number of customers, and other influencing factors. Nonetheless, these five planning steps should be used as the framework for the development of any meaningful water conservation plan.

The five steps are:

- Step 1: Profile of Existing Water Supply System – Collection and development of supply-side information and historical supply-side water efficiency activities.

- Step 2: Profile of Water Demands and Historical Demand Management – Collection and development of demand data and historical demand management activities.

- Step 3: Integrated Planning and Water Efficiency Benefits and Goals – Identification of how water efficiency will be incorporated into future water supply planning efforts and development of water efficiency benefits and goals.

- Step 4: Selection of Water Efficiency Activities – Assessment, identification, screening, and evaluation process to select and fully evaluate a portfolio of water efficiency activities for implementation.

- Step 5: Implementation and Monitoring Plans – Development of an implementation and monitoring plan.

Through implementation of the five steps, current water use and future demands can be analyzed, needs for infrastructure and facilities can be assessed and future water supply options can be identified. By utilizing the process outlined in the Municipal Water Efficiency Plan Guidance Document prepared by the Colorado Water Conservation Board, water efficiency program impacts can be integrated with water supply planning to create a more holistic approach to water resources management.

Resources

A drought management plan defines when a drought-induced water supply shortage exists and specifies the actions that should be taken both prior to a drought to lessen impacts and response actions following the onset of a drought. The main objective is to preserve essential public services and minimize the adverse effects of a water supply emerge ncy on public health and safety, economic activity, environmental resources, and individual lifestyles. Drought management planning includes the development of drought mitigation measures to help reduce or avoid drought impacts when a drought occurs and a drought response plan to implement when a drought is officially declared. The Colorado Water Conservation Board has developed the Municipal Drought Management Plan Toolbox that municipal water providers and local governments may use as reference tools in developing local drought management plans.

ncy on public health and safety, economic activity, environmental resources, and individual lifestyles. Drought management planning includes the development of drought mitigation measures to help reduce or avoid drought impacts when a drought occurs and a drought response plan to implement when a drought is officially declared. The Colorado Water Conservation Board has developed the Municipal Drought Management Plan Toolbox that municipal water providers and local governments may use as reference tools in developing local drought management plans.

The Guidance Document outlines the following eight steps that providers can use when developing their individual plans.

Any entity, including any municipality, agency, special district or privately or publicly owned utility or other state or local governmental entity, may submit a drought management plan to the CWCB Office of Water Conservation and Drought Planning (OWCDP) for review and approval.

Resources

Kansas Water Office Drought Resources

Colorado Water Conservation Board Drought Management Plan Guidance Document

An emergency preparedness plan dictates communications and actions that will be employed in the case of a set of stated, potential emergency conditions that may reasonably arise related to weather, terrorism, or other acts of god. An emergency preparedness plan is something that all operating organizations develop and maintain as current at all times. At a minimum, this plan should include:

- A list of local and state emergency contacts.

- A system for establishing emergency communications.

- Any mutual aid agreements the utility has with other communities for sharing personnel, equipment, and other resources during an emergency.

- Standard procedures for emergency water production.

This information should be made available to all those responsible for the operation of the water system, including staff, consultants, and Board members, to the extent necessary.

Resources

American Water Works Association Water-Wastewater Agency Response Network (WARN)

Integrated resource planning (IRP) is a vital component of utility planning linking supply-side and demand-side management assessments and program implementation into a comprehensive assessment and evaluation. IRP utilizes least-cost planning principles using an open, participatory process, to assess the benefits and impacts of water conservation and drought response on future water supply needs, alternative source water options, and capital improvement project requirements.

Key components of integrated resource planning are:

- Equal treatment of supply-side and demand-side options,

- Clear objectives,

- Consideration of supply-side and demand-side reliability,

- An open process,

- Integrating engineering analysis with a range of policy objectives,

- A planning horizon or future design year,

- Explicit consideration of uncertainty, and

- Demand monitoring.

IRP encompasses least-cost analyses of demand and supply options that compare supply-side and demand-side measures on a level playing field and results in a water supply plan that keeps costs as low as reasonable while still meeting all essential planning objectives. To this point, IRP process of integrating water conservation, drought planning, water supply development and demand-side management is fundamental to creating a successful, sustainable water resources management program for any organization with limited financial resources (CWW, 2010).

Integrated water resource planning combines assessments of demand management and supply resources to meet forecasted goals specified by the utility. To this point, developing the goals for any organization is vital to the overall IRP effort, since utilities must be able to articulate goals that are specific, measureable, achievable, reasonable, and attainable within a specified timeframe. Once goals have been defined, the IRP process uses various tools and analyses to evaluate key decision-making criteria that may include:

- Reliability

- Cost

- Environmental impacts

- Risks

- Public acceptability

Once identified and analyzed, scenarios are rated and ranked. Rating scenarios based on their ability to meet key objectives and comparing ratings can help determine which scenarios are more favorable. The Alliance for Water Efficiency offers a demand tracking tool to members that can aid planners in refining demand modeling data and in developing and comparing different scenarios (AWE, 2009).

Resources

Colorado WaterWise Council Best Practices Manual (with Section on IRP)

Incoming revenues define the viability and sustainability of any functioning organization. Water sales revenue will need to be designed to allow a utility or water company to operate its system, maintain compliance with relevant federal and state laws, conduct routine maintenance, pay off debt, and establish and maintain a reserve for future capital improvements. In addition, water rates and billing practices (see billing practices link) can be used to message customers regarding water waste and wise water use, since water rates and fees influence the community perception of the value of water. Low rates may promote water waste. Rates that are too high may create blight if outdoor irrigation ceases in some locations. Changing rates upward may also impact water customers that live on fixed budgets. Therefore, setting (and as importantly, changing) water rates has a social justice component that will always influence the process and in the end affect decision making at the Board level. Therefore water rates can impact utility revenue and customer demand.

Water rates and fees include the following, which are listed by common names but the actual name used by any specific utility may vary:

Service fee (base fee) – this is a fee that is charged each customer regardless of water use. It typically is used to cover administrative costs and other fees incurred by the utility, and it often includes an allowance for a minimum volume of water use (for example, a $24 base fee includes 3,000 gallons of water use prior to water rate costs being incurred by the customer).

Water rates – cost per volume of water used, typically on a price per unit volume (typically per thousand gallons, but some use per one hundred cubic feet, or other variations). Types of water rates commonly used include:

Uniform rate - a constant rate per unit of water is charged which does not change with the amount of consumption.

Descending (or declining) Block Rates – water rate per unit of water used decreases as more water is used. Historically this rate structure was used in various locations, most often to support large commercial customer needs; however given the status of water scarcity and increasing costs to produce, treat and distribute water in Colorado, descending block rates are considered inappropriate.

Ascending (or inclining) Block Rates – water rate per unit of water used increases as more water is used. These types of rates can encourage customer water use efficiency, if the block rates are substantially punitive (i.e., increase significantly) as water use increases.

Water budget - a variation of inclining block rates where the block size (i.e., the amount of water sold at a particular unit rate) is defined by an empirical determination of efficient use for each customer such as irrigable area. Water budgets are considered to be more equitable than inclining block rates especially in circumstances with different customer characteristics within a specific sector (e.g., having a group of residential customers with substantially different lot sizes; customer having different numbers of family members using a single household, etc.).

Seasonal or variable rates - higher unit prices are charged during periods of water scarcity (typically during the summer and fall, or in response to a drought, to reduce demand in times of water shortage and to encourage customer water demand reductions). Seasonal rates can be used to adjust either uniform rates or inclining block rate structures.

Tap or impact fees – these fees typically relate to the cost for a new tap to be installed at a home or business, and may include the cost of new water development and/or infrastructure associated with the connection.

Connection fees – these are typically the fees that occur when a new customer connects to an existing tap. New customer connection fees typically include administrative costs to begin and end billing and meter reading for a new customer.

Other Relevant Influences

The items described below influence how water rates are set and should be considered during water rate planning efforts.

Customer segments – many utilities develop different water rate structures and pricing for different types of customers, differentiating water use costs for single family residential from multi-family residential from commercial from irrigation or seasonal customers.

Water development costs – Some organizations with substantial growth will include water development fees in either tap and impact fees, or as service fees, or both.

Costs of service – The rule is simple: Charge rates that cover service costs; however, building a rates program that follows that rule is not so simple. Some utilities approach the task by identifying some specific customer classes and then determining the cost of providing service for each class. Based on that determination, rates are adjusted. A huge impact on the cost of service is peak usage. "Peak usage" means the largest amount of water the system is asked to provide all at once. The system cannot be built to provide average use; it must be capable of satisfying peak need. Costs to operate during peak use are therefore different, and higher, than operating during average use (for example, electricity costs increase during peak use).

- Cost of infrastructure improvements and repairs – All water utilities are faced with the cost of maintaining and replacing aging infrastructure. Different utilities are faced with infrastructure that consists of materials and equipment differing by age and quality. Therefore, each utility must develop a reserve from water sales revenues that allow for timing reparations and replacement (see Facility Assessment and Capital Improvement Planning BMP).

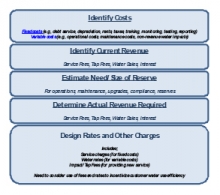

Setting water rates and fees should be considered as an ongoing effort continually being updated and improved, since costs and customer demands change constantly. The process of changing water rates and fees is provided in the figure.

Setting water rates and fees should be considered as an ongoing effort continually being updated and improved, since costs and customer demands change constantly. The process of changing water rates and fees is provided in the figure.

Setting water rates and fees involves data collection to identify costs and revenue sources; estimating future revenue needs (which includes the critical task of developing capital improvement budgets (see the Facility Assessment and Capital Improvement Planning BMP); and designing rates and other charges based on expected demand and customer needs.

Specific actions that are considered best management practices include the following, when setting rates:

- Water rates should cover all costs of service related to water delivery, as well as expected cost to maintain and upgrade the water infrastructure. For this reason, it is not typically appropriate to include “free water” as part of a base service fee, since the cost of water delivery is not necessarily included in the base service fee.

- The base service fee should include expected fixed costs (e.g., future capital improvement projects, current debt service, staffing costs, etc.), whereas water rates should cover all variable costs related to water delivery (e.g., energy costs, treatment costs, etc.).

- Water utilities should evaluate the benefits of developing inclining block rates or other conservation oriented rate structures when assessing water rate programs, to help create incentives for customer water use efficiency; however, inclining block rates will need to include substantial increases in charges to create punitive impacts (e.g., an inclining block rate with less than a 25% change between blocks does not create a cost signal that is impactful enough for most situations; with the top tier set at 200% of the base rate).

- Seasonal water rates should be considered for those water utilities that have challenges meeting peak day demands related to seasonal customer water use (e.g., summertime irrigation and/or cooling demands). Seasonal rates can be used to increase summertime water costs, sending a message to customers related to the cost of water and incentivizing customers to use water more efficiently.

Resources

US EPA Small System Water Rate Setting

American Water Works Resources on Utility Rates

Department of Local Affairs Technical Resources on Utility Rates

Colorado Water Wise Best Practices Guidebook

Georgia Environmental Protection Division – Conservation Water Rate Structures